While racing and land speed records were in existence before WWII, these speed activities blossomed after the war’s end. Motorsports growth can be attributed in large part to the experience and technological advancements from the war effort. Plus, there was a vast surplus of parts as the military sought to shrink down its inventories.

Almost overnight, hot rodders and racers took advantage of equipment and parts that were significantly more dependable and stronger than anything previously used in the automotive world. Aircraft-grade hardware became an essential item — and for a good reason — speeds were increasing on the tracks and dry lakes.

Commercial Vs. High Performance

Hardware sold for household and farm use was typically made from low carbon steel worked well for most residential use. This included the family grocery getter. Once the American automobile manufacturers returned to making cars instead of tanks and airplanes, pre-war hardware was not good enough for speed enthusiasts. These race car builders sought out aviation hardware, which implanted an idea implying the very best in design, materials, and quality control came from the aviation industry.

“Aerospace fasteners are not even close to good enough. – Chris Raschke

It is true that commercial-grade hardware from your local hardware or retail auto store should not be considered for aviation use due to lower tensile strength. The same is true of aviation bolts when it comes to high-performance race cars. If you’ve been around any high-performance engine, you probably know the name ARP (short for Automotive Racing Products). According to ARP’s Director of Sales and Marketing, Chris Raschke, “In racing, “aerospace fasteners are not even close to good enough.”

Most of the commercial hardware found at chain stores is inexpensive with low tensile strength, commonly in the 50,000- to 60,000-psi range, which bend easily and offers little to no corrosion protection. ARP uses materials and processes that produce bolts and studs from 125,000 to 270,000 psi out of corrosion-resistant steel. Use the high-performance hardware for high-performance applications and leave the commercial hardware for the riding lawnmower.

ARP’s quality policy is posted throughout the plant to ensure everyone is on the same path. It is a source of pride for every member of the team.

About ARP And Its Manufacturing Process

Gary Holzapfel started ARP in the late ‘60s to fill the need for commercial studs and bolts that were up to the challenge of high-performance racing. Holzapfel’s background in making aerospace fasteners helped with the creation of the new business as he benefitted from his history in creating his new shop. From those meager beginnings, ARP now occupies several different buildings in Santa Paula and Ventura, California.

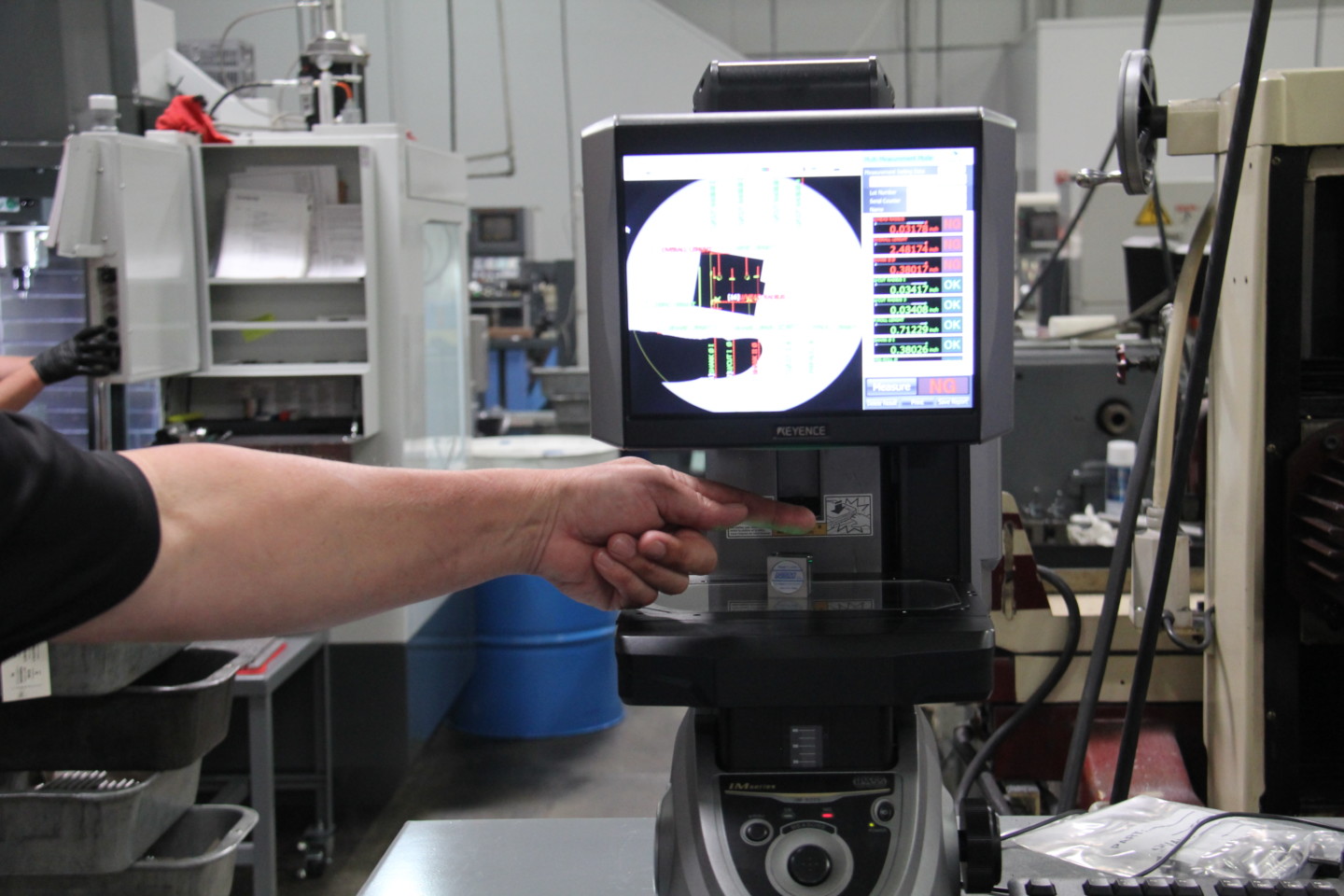

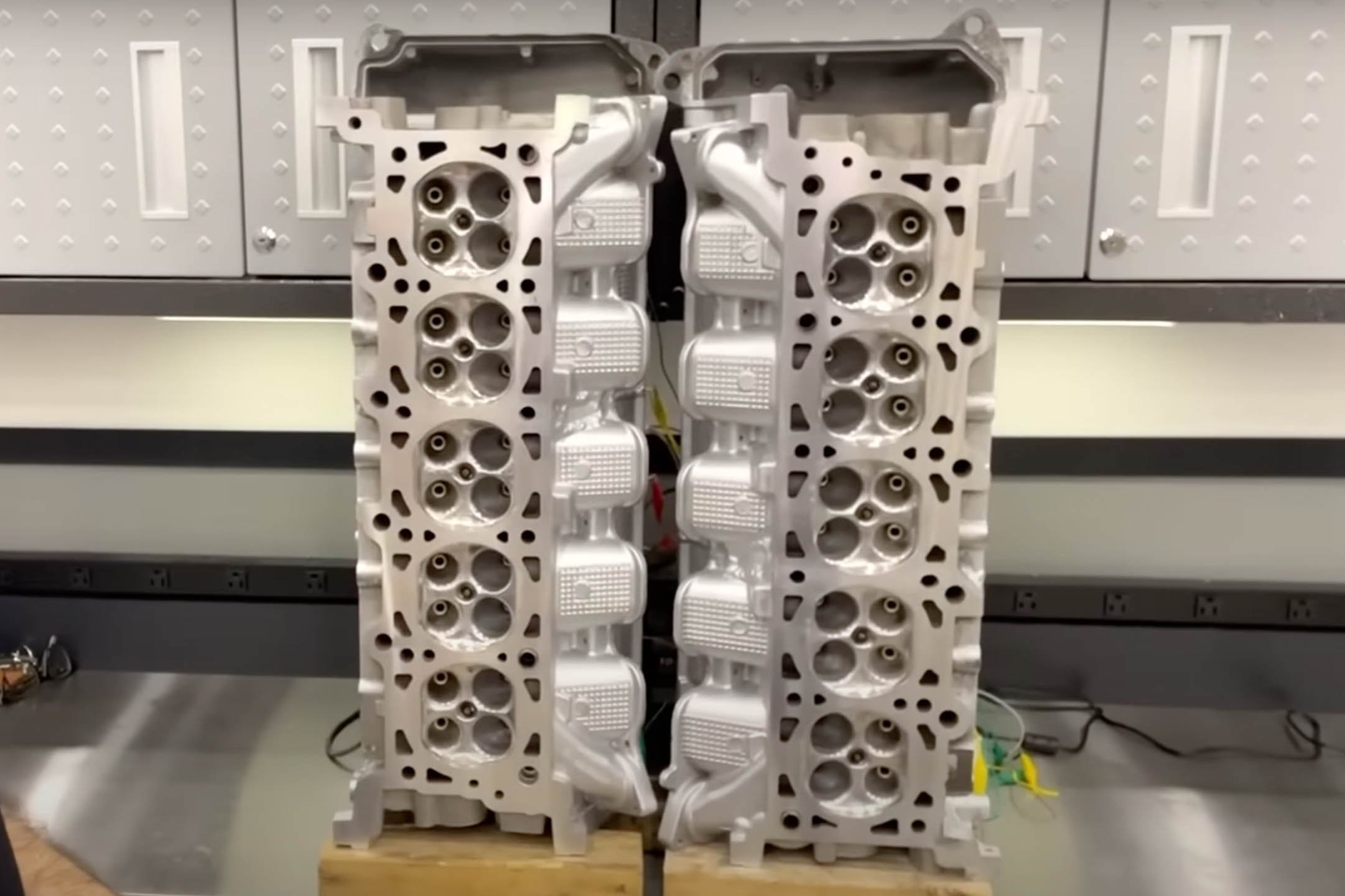

While most enthusiasts are very familiar with ARP’s connecting rod bolts and cylinder head studs, ARP makes a fastener for virtually any part on a car. It supplies specialty hardware to top Formula 1, IndyCar, NASCAR, and NHRA teams.

We make it a habit to stop by ARP Headquarters and talk to Raschke whenever we are in the area. Without fail, we are always impressed with the way ARP makes its fasteners. The complicated process never gets old and never gets boring.

The raw material is where ARP's chocolate chip cookie recipe starts.

Why ARP Fasteners Stand Out

Every time the question comes up, “What makes ARP fasteners different?” Raschke responds with his often-repeated chocolate chip cookie response. “Everything ARP makes is to a recipe, and you have to follow that recipe. If somebody says, ‘I can make an 8740 rod bolt just as good as ARP’…you need to look at it as a chocolate chip cookie. You can go out and buy a premix and get poor quality chocolate chips, and follow the instructions, and you’ll get a cookie in the end, maybe. But the ARP way is to purchase the finest ingredients, follow the recipe very carefully, and you’ll come out with a better chocolate chip cookie.”

To Raschke’s point, ARP controls all aspects of the manufacturing process from beginning to end, all under the ARP collective roofs in Southern California. Obviously, this limits any outside influence on the finished product and makes it easier to track down a problem before it becomes an issue.

ARP orders its raw materials, many of which are proprietary alloy blends, from one of the top foundries in the world. “Carpenter Technology Corporation in Reading, Pennsylvania, is the top-of-the-line,” said Raschke. Carpenter Technology is a recognized leader in the high-performance, specialty-alloy-based material applications in aerospace, defense, energy, and industrial industries.

As an example of top materials, Raschke used the popular 8740 Chromoly steel material to illustrate the point. “The mill offers four grades of this material,” he said. The first is a commercial quality, which is followed by an “aircraft quality” material. According to Raschke, “ARP uses only the top two grades,” which are SDF and CHQ.

The SDF and CHQ grades cost twice as much but provide for defect-free fasteners. These material grades are offered in bar stock and large coils. The bar stock is used to manufacture studs, and the coils are used to make bolts.

ARP's 9,000-square-foot warehouse is filled with raw material used to make fasteners. From spools of coiled wire to bar stock.

Where The Process Begins

The raw materials are stored in a 9,000-square-foot warehouse near the manufacturing plant. Making these coils of wire, or steel bar stock, into fasteners begins by moving the material into the plant, then starting the hot and cold heading processes. This is where the material is shaped into the rough form of a bolt with the bolt head and shank.

The coil is loaded onto a cold-heading machine where it gets straightened and cut to the proper length. Then, the head is formed under intense pressure from a high-speed press.

To achieve this, the raw material is loaded into forming machines that straighten the coils of steel, then fed into other forming machines either cold (cold forged) or heated by an induction heating process (hot heading). Powerful industrial machines shape the material under tons of pressure.

Heat Treating, Polishing, And Grinding

After the basic form of the fasteners is complete, the blanks are subjected to the heat-treating process. The fasteners are loaded onto a rack and put into a furnace — an Internal Quench Furnace to be exact — where the operator heats the fasteners to a set temperature for a specific time. The time the material spends in the furnace is part of the chocolate chip cookie recipe Raschke referred to earlier.

After the fasteners have been heated for the prescribed amount of time, the parts are washed and moved to a draw oven where the hardness of the fastener is set. Different Rockwell hardness levels are required for different strength levels, depending on the intended application of the fastener.

The fasteners are taken to a noisy, and segregated, part of the plant where they are polished in large vibratory tumblers filled with various abrasive media. These tumblers debur the un-machined fasteners, and polish the stainless steel ones.

Fasteners destined to become studs are sent to the grinding department where they are centerless ground to ensure they are perfectly concentric. This is a time consuming and delicate process that can take as many as ten machining steps to get to the proper level of concentricity. ARP has several machines set up in the centerless grinding area to attain the highest level of accuracy for the many different types of studs offered by the company.

Big round vibrators loaded with various types of material are used to debur the fasteners or polish the stainless steel ones.

Thread-Rolling

Bolts and studs move to another station where the thread-rolling operation takes place. Thread rolling is purposely done after heat treatment to maintain material strength. Fasteners threaded prior to the heat treatment process experience a loss in fatigue strength — up to ten times of those threaded after the heat treatment. Due to the different sizes, thread pitches, and types of threads, ARP has several different types of machines that roll threads, depending on the type of fastener.

The art of thread rolling is a sophisticated ballet between the machine operator and the equipment.

Rolled Threads Vs. Cut Threads

It cost more to cut threads, either with a die or on a lathe, because of the labor involved. It would seem that cut threads would be better because of the cost, however that is not true. Rolled threads are stronger because their grain flows in more than one direction as it follows the contour of the fastener.

Besides, rolled threads are smoother than cut threads, which allows for a more precise torquing process. A fastener that has rolled threads should never be re-cut with a die. This can affect the heat treatment and any plating or coating. Re-cutting threads reduces the amount of material on the shank of the fastener, which can cause a loss in strength.

Making A Nut

The other half of the fastener equation is slightly different. When it comes to manufacturing the nuts, ARP’s manufacturing process is another multi-stage process. The raw material is loaded into a huge forming machine that makes blanks of hex and 12-point nuts.

Once the blanks are formed, they go through a very sophisticated automated threading machine that taps each nut with an accuracy of .001-inch — which is five-times higher than aerospace standards. Remember Raschke saying Aerospace fasteners “are not even close to good enough?”

After the nuts have been threaded, they go to metal finish for either black-oxide coating for the Chromoly, or the polishing station for stainless steel nuts. Watching the process, it was evident that making a nut was far more complicated than making a stud or bolt.

Coating And Quality Control

Rust never sleeps, and steel is prone to rust. Rust is another name for iron oxide, which occurs when iron, or an alloy containing iron – like steel – is exposed to oxygen and moisture. Eventually, oxygen combines with the metal and forms a new compound oxide. This compound weakens the metal.

To delay this oxidation from starting, ARP coats its fasteners with a black oxide, which helps resist further oxidation. Raschke claims that the coating is nothing more than an appearance item. Because stainless steel is naturally corrosion-resistant, fasteners made by ARP from stainless steel are polished to a bright finish.

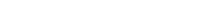

The quality control department makes routine destructive tests on random fasteners selected off of the line. The company has a room full of equipment that tests and measures the tensile strength of the fasteners. “In this room,” Raschke said, “All we do is rip stuff apart.”

The final-stage fasteners go through a series of quality control (QC) monitoring through special checking devices, which ensure they are within tolerances. Monitoring threads on studs, bolts, and nuts, is the most significant concern in the QC department. For every thread size, there is a checking device, and several steps to quality inspection.

That’s How It’s Done

ARP fasteners tend to be more expensive than most of the off-shore manufactured bolts, for good reason. Now that you understand the complicated process ARP uses to produce its premium fasteners, it all makes perfect sense. You get what you pay for.

This is only a small part of what ARP does on a daily basis. The company also has a very prolific Research and Development department who aggressively seek out new fasteners, tools, lubrication, and torquing aids to perfect the chore of mechanically joining two objects together. Shipping all of these products worldwide requires another full department focused on that single task.

We can’t answer for the rest of the industry, but when we spend our hard-earned money, we want the best chocolate chip cookie money can buy. Speaking of cookies, ARP also houses an award-winning restaurant on-site. Hozy’s Grill has become a favorite destination of “foodies” from all over the country. A car cruise to the ARP facility is well worth the time.