We’re back with another round of our engine-building endeavor for our Ultra Street effort. If you haven’t been following along with our build, let me give you a quick refresher. We basically let our hearts talk over our finances, and we purchased a well-used street bruiser. While the chassis worked great for what it was, we had to refresh it to pass tech without paying the track operator under the table. Besides, safety squints only work so well at 150 mph.

With the chassis finished up, we moved on to the engine build. In our first installment on the Ultra Street engine, we discussed building a solid foundation with a proper block and selecting suitable internals. Since our goal is to remain competitive in Ultra Street, we had to ensure that the block and internals possess the strength required for the amount of boost we plan on pushing through it.

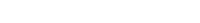

Speaking of boost, we needed heads that could keep up and flow the amount of air needed to propel us into the winner’s circle. In this segment, we’ll be putting on our dunce caps and letting Bennett school us on the right camshaft and valvetrain to stay ahead of the pack.

Camshaft Machining And Size

You can often discern the expertise of engine builders by their camshaft choices. Bennett understands the significance of a proper camshaft combination and has been testing various camshaft theories and experimenting with over a hundred different combinations to perfect setups in Ultra Street and X275 race cars. After all, a camshaft is no different from the entire race engine; everything needs to work in conjunction to maximize efficiency and performance.

For a camshaft, Bennett starts with a 55mm core. However, merely grinding a 55mm core to a specific size is not all that happens behind the scenes. After grinding, it received COMP Cams’s “Micro Surface Enhancement” (MSE) option. “By utilizing uniform pressure across the camshaft lobe face, MSE reduces the surface waviness common with other finishing techniques, such as belt polishing. The resulting camshaft surface more evenly distributes load for increased durability. Spreading the contact area between the roller and camshaft face allows for much higher loads and lower localized stress,” Bennett explains. “MSE also eliminates sharp edges and microscopic machining marks that typically result from the grinding process.”

Bennett continues, “Additionally, MSE utilizes uniform pressure across the camshaft lobe face, reducing the surface waviness common with other finishing techniques, such as belt polishing. The resulting camshaft surface more evenly distributes load for increased durability. MSE also eliminates sharp edges and microscopic machining marks that typically result from the grinding process.”

While the machining portion of creating a camshaft is intricate, formulating the right camshaft lobes plays an important role. “Ultra Street engines are very finicky about camshafts. I’ve seen 75-horsepower swings with just 2-3 degrees at .050-inch lift,” Bennett details. “The camshaft lobes we have developed for these engines are one avenue of our success, as we manipulate many aspects of the engine and the turbo with lobe design. I can have five camshafts with the same specification at .050-inch lift and lobe separation, and every camshaft will run differently based on the lobe design.”

The most common error we observe in engines we reconfigure for customers is the use of excessive spring pressure, which ultimately reduces power. — Jon Bennett, Bennett Racing Engines

Once again, understanding the entire combination to maximize efficiency and generate more power is crucial. “Knowing what spring pressure, rocker ratio, and pushrod size work the best is another key to the camshaft equation,” Bennett details. “From the spring side, we examine how little spring pressure we can run and still control the valve. The most common error we observe in engines we reconfigure for customers is the use of excessive spring pressure, which ultimately reduces power.” This leads us to the next portion of our Ultra Street engine build: the valvetrain.

Controlling The Valves

An engine is only as strong as its weakest links, and we’re aiming to identify and address those weak links during the build stage rather than trackside. While not as challenging to access as other engine internals, we still don’t want a broken lifter or bent pushrod ruining one of the few days we have to go racing. Therefore, Bennett specified a combination that will work with our power goals and our camshaft selection.

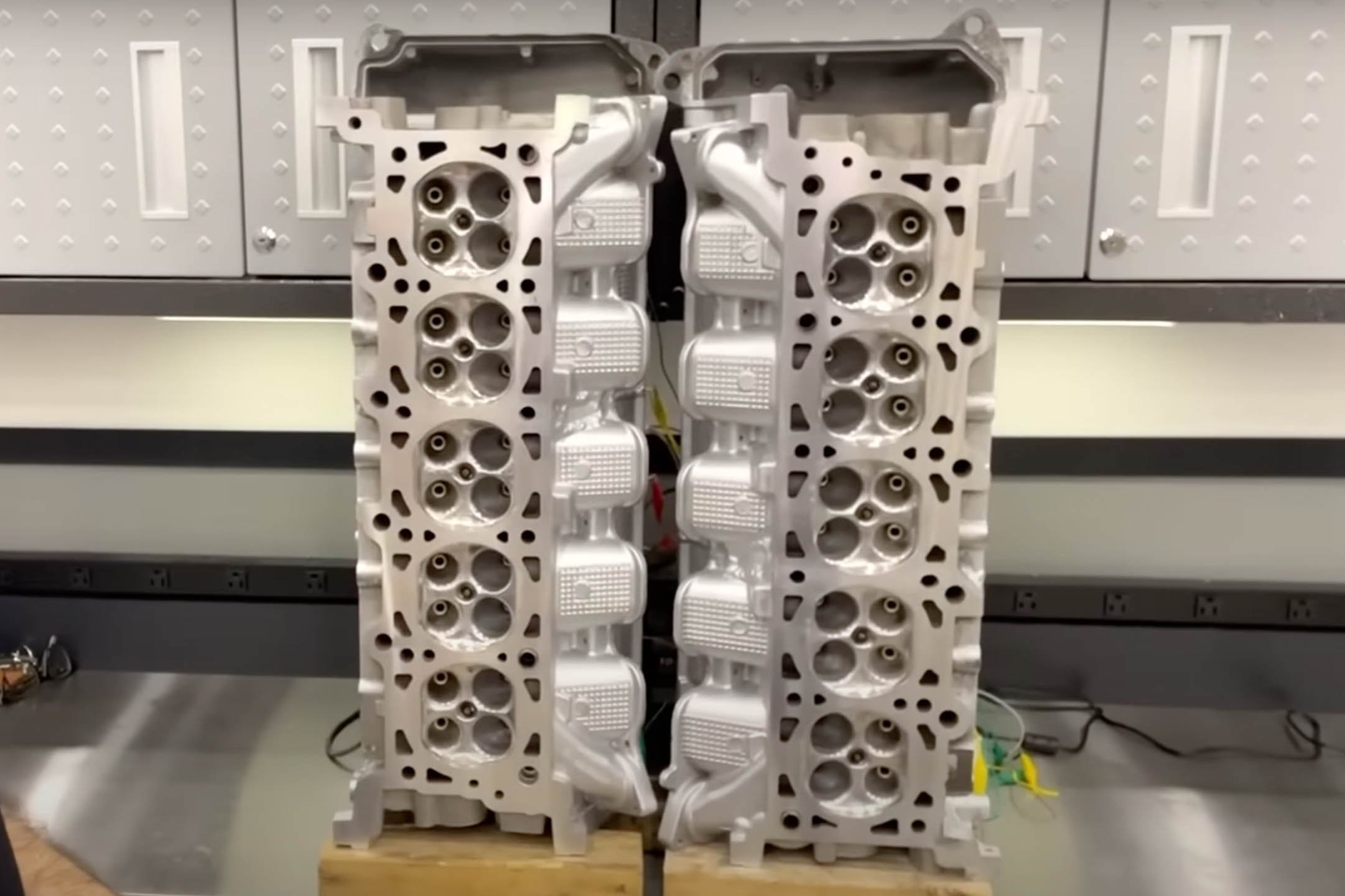

Transferring the force from our camshaft to the pushrod is a set of Jesel lifters, a brand that Bennett relies on for all engine builds. In our build, Bennett used a .905-inch diameter for the lifters. “We use an offset exhaust and a centered intake for our Trick Flow 265 heads and our version of the Jesel rocker,” Bennett explains. “This setup allows us to use a 7/16-inch diameter pushrod without breaking through the pushrod tube of the cylinder head.”

“For this and most Bennett Racing Engine builds, we use Trend Performance pushrods. We opted for a 7/16-inch diameter pushrod with a .165mm wall thickness. This pushrod is durable with minimal deflection,” Bennett explains. While most Trick Flow Specialities High Port-equipped engines cannot accommodate a 7/16-inch pushrod, we have developed a lifter and rocker design that allows us to do so without compromising the head port. We have run these combinations up to 9,500 rpm without issue.”

We once again turned to Jesel when it came to our rocker arms, but instead of selecting off-the-shelf rocker arms from the catalog, a set was sent specifically made for the Bennett Trick Flow Specialties High Port 265RX cylinder heads. “This rocker arm features a bigger and beefier stand with a height sized for our valve length, eliminating the need for shims under the stand like many are forced to use due to different valve lengths in Trick Flow High Port heads in general,” Bennett explains. “We also opted for a steel rocker version to provide this Ultra Street engine with more strength and a longer life cycle.”

Springing Into Action

One of the essential components of the valvetrain is the springs. As Bennett mentioned earlier, many builds that come through the shop are often oversprung, robbing horsepower. “For this build, Performance Springs Incorporated 1254 springs were chosen based on the desired spring pressure and cam lift,” Bennett explains. “This spring exerts 350 pounds on the seat and 1,040 pounds when open. We expect to get 80 to 85 passes with these springs, but we have seen many engines come back with 100 passes and very little change in spring rate.”

However, Bennett is quick to dispel any concerns about not running enough spring pressure. While some might ask, ‘why not higher pressure springs?’ “Simply put, you do not need extreme spring pressures on these types of small combinations,” Bennett says. “Yes, our max-effort nitrous and blower combinations with the 265RX have more spring pressure, but that is based on coil bind needs, not the actual pressure needed. Many springs that give us the coil bind room, say for a .990-inch cam lift, just are not available in lower pressures. So, we are forced to use a spring with 25 to 50 more pounds of seat pressure than we need.”

Bennett continues, “All of this is based on the 265RX head, which has an intake valve that is lighter weight due to its shorter length and smaller head diameter. When you move into a more exotic small-block head like an Edelbrock SC1, CID SC2, or our billet head, more pressure is required simply due to having a valve that is over one inch longer and has a bigger head diameter. That valve is much heavier and requires more spring pressure to control it at high-RPM and/or high boost levels.”

Victory Valves

Our final step in the valvetrain was installing the valves. “We use valve head sizes ranging from 2.125 to 2.180 inches for the intake. We also have a new 2.180-inch version that has offset guides to achieve larger valves for racers spraying a lot of nitrous or running powerful naturally aspirated engines. Some of these naturally aspirated combinations make 940 horsepower on motor alone,” Bennett says. “Victory 1 Valves are our Inconel exhaust valve of choice in the 265RX heads, but we have also used Ferrea high-temperature exhaust valves.”

Throughout the valvetrain, we used Manley Performance titanium retainers and locks, Xceldyne spring locators, and Manley Nitro lash caps. Bennett explains his choices, saying, “we use lash caps in many of our builds to protect the valve tip should a rocker tip fail. By doing this, the valve tip is not damaged, and you can simply replace the lash cap and change the rocker instead of pulling the head and changing out the valves.”

Only As Strong As Your Weakest Link

We aimed to eliminate any problems that could arise during racing while also keeping costs down with extended replacement intervals. Bennett’s wealth of knowledge once again astounds us as we continue to build the ultimate Ultra Street engine. Stay tuned, as next month we’ll be discussing timing and completing the remaining bits of the engine before we hit the dyno!