When discussing air induction, it seems like aftermarket intake manifolds get all the love. With modern-day machining technologies and airflow testing procedures, we can see why the latest and greatest air induction upgrade can seem so appealing. But let’s save the new product drop news blasts for our annual SEMA and PRI coverage showcases because today we’re talking about OE intake manifolds.

A crucial core component on the upper end of the engine, air intake manifolds play a crucial role as the catalyst that turns fresh atmosphere into sectioned servings of high-velocity air. And while the entire topic of how these vital portions of the modern combustion engine have been covered in great detail here at EngineLabs over the years, we have yet to discuss the oddball intake manifold.

These are the ugly ducklings of the flock. The black sheep of fresh-air feeding time. Often adorned with elaborate, or even bizarre configurations, with a single goal in mind: Making more power and efficiency possible, while still fitting within the engine bay and not receiving a red card for emissions or some other form of tomfoolery.

Into the Ford Taurus SHO Snake Pit

It may seem like ancient history by today’s standards, but the first iteration of the Ford Taurus SHO was pretty damn brilliant. First made available in the 1986 model year, the performance version of the Taurus rocked one of the wildest intake manifolds of all time right on top. Commonly called the “Super High Output” Taurus, this unassuming sedan was the world’s most powerful front-wheel-drive production car when it made its debut.

Part of the reason why this sedan was so swift, was because of its 3.0-liter V6’s ability to breathe. Ford tapped Yamaha to help engineer much of the SHO engine, and since baby grand piano stringing and MotoGP engineering can grow a bit tiring day after day, the Japanese firm decided to blow off a little steam by getting creative.

What emerged was a variable-length intake manifold so expansive, that it cradled almost the entirety of the upper end of the engine. With a duo of interconnected plenum chambers and a dozen intake runners. Each plenum pulled double-duty by providing air to three short and three long runners as needed. While the short runners took care of any cylinder business below the plenums, longer runners snaked outward to provide fresh oxygen to the opposing cylinder bank. This provided a near-perfect balance between horsepower and torque.

Anywhere below 4,000 rpm, butterfly valves in the short runners would snap shut, allowing the long runners to do all of the heavy breathing for improved torque figures. Anywhere beyond those revs, the short runners would come to life, with fresh air being fed to all twelve tubes.

This resulted in 220 horsepower and 200 lb-ft of torque being channeled to an exclusive Mazda stick shift, with power soaring all the way into the 8,000-rpm range. Ultimately, this resulted in a bunch of driveline accessories failing earlier than expected, so Ford’s engineers opted to drop the SHO’s redline down to 7,000 rpm just to be safe. Even then, 0-60 times consistently hit 6.6 seconds, and with 143 mph being the engine’s top-end speed, the first gen Taurus SHO’s power figures were referred to as “contemporaneously strong” for the era in which it arrived.

The Classic Chrysler Cross-Ram

Decades prior to Ford making the Taurus SHO, the Chrysler B-block of the 1960s was about to get a major upgrade: The iconic “Cross-Ram” air intake manifold. Utilizing a set of dual four-barrel carbs, this design pivoted the tubes across the engine, where they hovered above each exhaust manifold. All of this oxygen was then sent spiraling down a 30-inch runner system to the opposite bank, where it was fed into its appropriate intake port. Hence the name “Cross-Ram” is such an appropriate designation.

Take a quick glance at this impressively detailed synopsis of the original Chrysler Ram intake manifold, and you will realize that the engineering behind this overlapping air induction design was pretty revolutionary for its time.

Since this design was intended for production cars, each Cross-Ram unit was easily interchangeable with the stock intake manifold and therefore could be swapped on at any dealership. Utilizing an aluminum long-tube cast design, each bank of the venerable V8 relied upon its own dedicated Carter AFB four-barrel carburetor. For hood clearance purposes, each intake manifold runner was cast in such a way that it hung over the valve covers, with a balance tube bridging the two manifolds for a smoother idle and cleaner startup.

This ended up netting 310 horsepower in 361 Cross-Ram form (at least according to Chrysler), and due to its easy installation and uniform design, quickly became a go-to bolt-on mod in the hot rod community. Naturally, there were issues with heat-soak due to the intake manifold’s position above the heads and the exhaust manifolds, as well as high-RPM limitations, but no biggie. A stock Cross-Ram commuter car had the ability to generate 435 pound-feet of torque courtesy of those insanely long (and strange) intake runners, so most people didn’t seem to mind whatsoever.

Nissan’s VH V8 Face-Hugger Intake

It may not be nearly as complex, or as lengthy as the previous two intake manifolds on this list, but the air induction unit that powered the Infiniti Q45 was pretty damn wild looking.

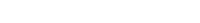

Commonly referred to as a “face-hugger” due to resembling the egg-laying offspring from the Alien movies, the intake manifold of the Nissan VH series of V8 engines is instantly recognizable. This is due in part to the alignment of the engine, which is a longitudinal (front to back) V8.

Since powering the rear wheels was this Japanese-made V8’s sole purpose in life, it is incredibly odd that Nissan’s VH engine’s intake manifold was positioned in such a way that it resembled a front-wheel-drive configuration. Speculation as to why this design was chosen runs rampant, and no one seems to have a concrete answer. Even I was unable to secure any insight into the subject while visiting Nissan headquarters in Yokohama a few years back. Whatever Nissan’s engineers had been cooking up all those decades ago has long since been sealed up in a dusty vault somewhere or lost in the annals of automotive history.

Being that the VH motor was engineered for domestic Japanese platforms before all others, the most logical explanation would be that it was done to meet Japan’s exceedingly strict JCI inspection/DOT standards, or shaken (車検) as we call it over here. Perhaps hood clearance concerns played a role as well, but either way, what a beefy-looking air intake manifold!

The Iconic C4 Corvette TPI Intake

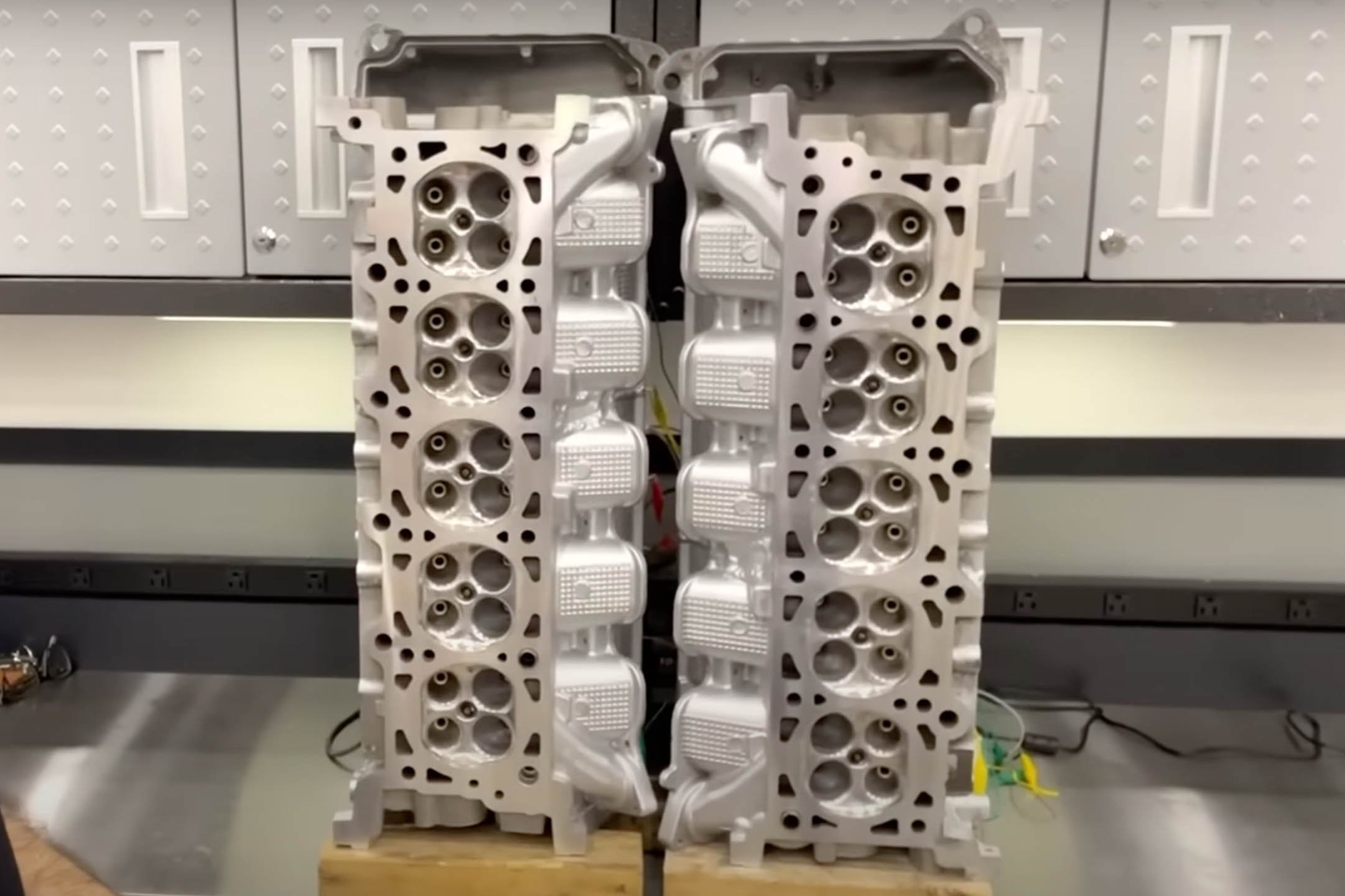

Finally, we get to an engine that struggled with meeting American emissions regulations, because all it wanted was to go fast. Yes, I am talking about GM’s electronically-controlled, fuel-injected, Tuned Port Injection (TPI) intake manifold.

With its intricately long, smoothly curved runners bridging the plenum to the lower manifold, this torque-rich design came tuned to perform in response to electronically detected air charge velocities in the low-to-mid-RPM range. This allows the intake valves to remain closed until the last possible split second when they snap open to allow the denser charge of high-velocity air to hit the chamber.

Unfortunately, due to the restrictive emissions standards of that era, the C4 Corvette was bottlenecked in almost every other department and generated just 245 horsepower on a good day. However, thanks to this TPI design, a full 345 pound-feet of torque was dumped into the rear wheels. The only issue? Ravenous packs of roaming American-engineered electrical gremlins feeding on 1980s-grade materials. Still, what a badass-looking intake manifold this thing was with its shrouding removed!